From the moment we are born, to the moment we die, we spend our time wanting things.

But we never stop to ask, “Why do we want what we want?”

Wanted well not an ability we are born with; it is an ability we must develop over time. Each of us will occasionally face a multitude of competing desires: Take job offer A or B? Start a new relationship, or stay single? Have kids or enjoy a few more years of sleeping in?

Our desires shape our lives. We spend energy, time, and other valuable resources pursuing what we desire. Picking the right desires is fundamental to achieving the outcomes that truly matter to us.

This inspired me to ensure that my desires are aligned with the life I want. If, like me, you’d like to get a deeper understanding of your desires and take greater control over them read on.

Needs And Wants

When trying to understand desire, the best place to start is by defining needs and wants.

Understanding needs is intuitive. Needs are based on a biological foundation.

We need calories to burn. We need shelter to survive. We have a biological instinct for needs. If I am thirsty, I don’t need anyone to show me that water is desirable. We can rely on our biological foundation to guide our needs.

Needs can be equated to the first two layers of Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs. [1]

Bottom two layer’s of Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs

But after meeting our basic needs, we enter the realm of human desires. And knowing what to want is much harder than knowing what to need.

Desire Is Mimetic

“Man is the creature who does not know what to desire, and he turns to others in order to make up his mind” – René Girard

No one has grasped the mystery of desire better than René Girard, former Stanford professor, author and historian. Girard spent much of his academic career studying and writing about desire.

Girard discovered a peculiar feature about desire: Desire is not something that we completely control ourselves. It is largely a product of a social process.

Prior to understanding Girard’s work, I assumed that I chose my desires. The truth is that desire is mimetic.

Mimetic comes from the Greek word “imitation.” Mimetic desires are those that we copy from the people and culture around us. When we broadly examine the effect of imitation on humans, this isn’t surprising. We learn through imitation. Speaking a language, operating by a common set of cultural norms, and playing a game are all examples of things we learn through imitation. We also learn what to desires through imitation. It turns out that imitation plays a far more important role in society than most people realize.

Girard called the people and culture that are the sources of our mimetic desires models.

You might be wondering, “Why do we rely on models as the source of our desires?”

In the realm of desire, there is no clear hierarchy. We don’t have a biological compass to help guide our decisions regarding what job to take, what lifestyle to live, or what to pursue. So, we rely on models. Models help us assign value to subjective things. When another person wants something, we assume it is valuable and worth pursuing.

We have all experienced the power of mimetic desire.

Imagine that you walk into a sneaker store with your friend, Aaron. The store has racks filled with hundreds of shoes. After browsing, nothing sticks out to you, but Aaron becomes enamored with one specific pair of sneakers. Suddenly it is no longer just a pair of shoes; it is the pair that your friend, Aaron, chose—the same Aaron who understand street style. The sneakers have now been transformed. They are a different pair of shoes than they were five seconds ago, before your friend started wanting them. [2]

This is mimetic desire at work. You can replace the shoes with anything: a new promotion, an extravagant wedding, a friend buying a house. As soon as someone in your circle wants and gets these things, you suddenly want them too. Desire is mimetic.

Becoming Anti-mimetic

My journey to finding Girard and learning about mimesis was driven because I want to live an authentic life.

I felt especially vulnerable to the mimetic herd because my entire career has been in competitive professional jobs. In such environments, it is easier to be influenced by your peers, adopt their desires, and accept external definitions of success. While I enjoy competition, I don’t want to fall into the trap of competing for the sake of competing. I want to compete for something worth pursuing.

From my experience, two things make you become anti-mimetic: understanding your models and changing how you think about desire.

Understanding your models

The first step is to identify who is influencing what you want––to identify your models.

Girard identified two main types of models: internal and external.

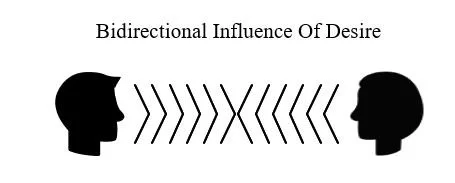

Internal models are people inside your world. They are your friends, co-workers, family, or anyone else you interact with in some meaningful way. This relationship is defined by a bidirectional influence of desire—they influence your desires, and you influence theirs.

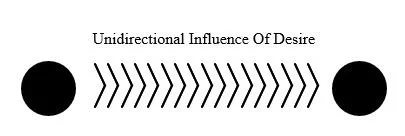

External models are people outside your world. They are people who you have no realistic way of encountering, such as celebrities, icons and historical figures. Here, the relationship of influence is unidirectional. They can influence your desires, but you have no way of influencing theirs.

The classification of internal and external is important because the type of influence these models exert on us differs. The influence that internal models exert is typically negative. Their influence can cause unnecessary competition and the pursuit of empty desires.

For example, who are you more jealous of? Elon Musk, the world’s richest person? Or someone you went to school with, who makes $30,000 more than you, has a better job title, and recently bought a Tesla? It is likely the latter. The difference can be explained by internal and external models. [3]

Working out who your internal and external models of desire are will help you gain better control over which desires you adopt. My reflection uncovered five friends and acquaintances who I often compare myself to. Having better visibility here allows me to ensure that I don’t blindly adopt their desires and that I approach our relationships with gratitude instead of jealousy.

Desire is a spectrum

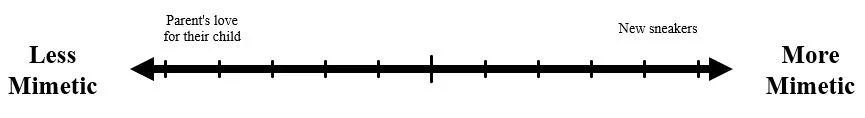

Is all desire mimetic? This is an ongoing debate among Girardian scholars. It is best to think of mimetic desire as a spectrum.

To the left are desires that are not mimetic at all. Non-mimetic desires would be those that are deeply rooted in who you are. They aren’t easily variable based on encounters with models, or experiences. You can think of a parent’s love for their child as an example. On the right side are desires that are extremely mimetic (T-shirt, investment FOMO, cars, etc.).

Authorship over your desires

Even though desires are mimetic, we can still have some authorship over them. For example, one of my goals is to write a book. Where did this desire come from? No one wrote books 1,000 years ago. My desire to write a book is based on my models. Many other desires such as starting a company or changing careers, are also the products of social interactions. However, that doesn’t preclude you from putting your mark of authorship on that desire.

By understanding your core motivation, you can better cut through mimesis. One of my core motivations is a combination of intellectual curiosity and expression. This is why I enjoy writing essays so much. However, intellectual curiosity is most satisfying if I find an outlet to express my understanding of a topic. Since I know this about myself, I can ensure the projects I commit to will provide an opportunity to learn and express myself.

The point is that desires have numerous influences, some mimetic and some non-mimetic. The goal is to understand who and what are influencing your desires and whether they are desires you want to own and cultivate. It doesn’t matter if they were originally mimetic, what matters is that they are important and align with who you are. This way, you can live an anti-mimetic life.

Notes, Inspirations & Additional Readings

-

Thanks to Kerri, Scott & Charlotte for their review and feedback.

[1] You can learn more about Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs here.

[2] This example is inspired by Luke Burgis and his book Wanting. This essay is heavily influenced by Luke. I recommend you check him out.

[3] An interesting question to ask yourself is: Is anyone I would like to see not succeed? It is likely that person is a negative model of mimetic desire for you.